Positive psychology is the study of “what makes life worth living.” If you want to be a hobbyist and read some research, this is a great place to start, as it can measurably improve your life. It’s worth noting that positive psychology arose in part as a reaction to psycho-analysis and behavioral analysis, but is not a rejection of those schools of thought—rather, it’s concerned with a different goal: how do we live the good life?[1]

What is the flow state?

Mihály Csíkszentmihályi—who I’ll refer to as MC because (a) damn and (b) it makes me feel like he’s a 90s hip hop artist into positive psychology--is a giant in this field. He defined the “flow experience,” which is a state in which a person engages in an activity and is fully immersed in it, feeling energized, involved, capable, and absorbed by it. In this state, it is common for us to feel as if time has passed incredibly quickly, and to lose a sense of space (and even, MC would argue, consciousness of one’s own existence). Colloquially, flow state is known as being “in the zone.”

MC and Jean Nakamura identify at least 6 independent conditions of flow state (i.e. they can occur independently, but only some combination of the factors constitutes a flow experience):

Intense and focused concentration on the present moment

Merging of action and awareness

A loss of reflective self-consciousness

A sense of personal control or agency over the situation or activity

A distortion of temporal experience, one's subjective experience of time is altered

Experience of the activity as intrinsically rewarding, also referred to as autotelic experience

Flow state is like positive hyperfocus—an optimal experience--according to MC.

How ‘bout some neuroscience?

In his Ted Talk, MC suggests that a person’s mind can attend to only a certain amount of information at a time: about "110 bits of information per second.” Just decoding speech takes about 60 bits of information per second—which is why we are really bad at understanding two simultaneous conversations. To some extent, flow state may be understood as a heightened focus on a given activity beyond what is normally achieved.

Steven Kotler suggests that flow state is associated with a cascade of neurochemical changes: your brain produces norepinephrine, dopamine, anandamide, serotonin, and endorphins. This chemical release may allow you to take in more information, process it more quickly and deeply (i.e. with more parts of your brain), and experience a heightened state of awareness. In addition, these chemicals may considerably improve motivation, and augment creative processes by improving our ability to combine new information with that which we already know. Pattern recognition may also be improved.

What are the benefits of accessing a flow state in daily life?

Though causality is notoriously tricky to prove in positive psychology, there is strong empirical evidence that time spent in a flow state makes us considerably more happy and successful.

People who have experienced flow describe it as:

Completely involved in what we are doing - focused, concentrated.

A sense of ecstasy - of being outside everyday reality.

Great inner clarity - knowing what needs to be done, and how well we are doing.

Knowing that the activity is doable - that our skills are adequate to the task.

A sense of serenity - no worries about oneself, and a feeling of growing beyond the boundaries of the ego.

Timelessness - thoroughly focused on the present, hours seem to pass by the minute.

Intrinsic motivation - whatever produces flow becomes it own reward.

I’m also willing to bet that you already know all of this, and can think of a time when you experienced flow, and the calm, focused, and life-affirming feelings associated with it. I’ve experienced flow state while performing jazz drumming with a good group, racing a car around a track, dancing, playing squash, fencing, and making jewelry. Though I have yet to see research on this, sex is likely a common way to access flow state.

Beyond the massive benefits of generally being happier and more content, flow state has a very well documented correlation with incredible success and achievement in creative and athletic endeavors, including artistic and scientific achievement, teaching, learning, and sports.[2] Of course, to an extent, prowess in those endeavors makes flow state more likely, but many of the outstanding performances that one can think of in any endeavor likely had a component of flow state involved. It expands capability.

If it was possible to bottle flow state, it would be among the most powerful performance enhancing drugs imaginable. Deep focus, quicker thinking and reactions, improved connectivity between brain and muscle control, and enhanced pattern recognition would very likely lead to incredible performance. It seems to do just that: Michael Jordan, Carmelo Anthony, and Kobe Bryant all have strikingly similar descriptions (or perhaps a lack of descriptions—it’s an ineffable feeling) for being “in the zone.”

Ayrton Senna, late Formula 1 driver and a particular hero of mine, described qualifying for the Monaco Grand Prix in 1988 in the following way: "I was already on pole [...] and I just kept going. Suddenly I was nearly two seconds faster than anybody else, including my teammate with the same car. And suddenly I realized that I was no longer driving the car consciously. I was driving it by a kind of instinct, only I was in a different dimension. It was like I was in a tunnel [...] the whole circuit was a tunnel. I was just going and going, more and more and more and more. I was way over the limit, but still able to find even more."

Beyond performance, there is an immediate and lasting impact on happiness. MC began his research by looking into artists and then scientists—people who didn’t gain fame or fortune from their work, but were nevertheless happy. One composer shared his experience of flow: “You are in an ecstatic state to such a point that you feel as though you almost don’t exist. I have experienced this time and time again. My hand seems devoid of myself, and I have nothing to do with what is happening. I just sit there watching it in a state of awe and wonderment. And the music just flows out of itself.” MC’s interviews with the composer suggest that this experience is so intense that the composer feels almost as if he doesn’t exist—and despite that rather romantic notion, it’s the aforementioned limitations of our nervous system that cause the feeling. Someone truly engaged in creating something new doesn’t have enough attention left over to feel hungry, tired, or worried about bills—he’s focused on the music flowing out.

My sense is that there is something innately human about this. Peak achievement, the act of creation, the rare feeling associated with doing something that few others can do—there has to be a regular motivation for wanting to achieve on this level despite the difficulty and dedication it takes to do so. A feedback loop makes sense—it feels good to do this, and doing this makes you better, which makes you feel good. MC’s research also revealed that people who regularly access flow state report higher levels of happiness overall. Isolating exactly why this is is the purview of further research, but we can all benefit from the knowledge, without having a perfect explanation of the mechanism.

How can I access flow state?

Here’s the thing: flow—or totally losing yourself in an activity—isn’t exclusive to athletes and artists. MC has found it in CEOs, assembly line workers in auto factories, Navajo shepherds, mountain climbers, and more. Think your job isn’t conducive to some sort of flow? MC described one man he interviewed who worked in New York City, slicing salmon for lox and bagels at a Deli:

“...and he describes how you take a fish, a 30, 40-pound salmon, and you drop it on the counter, one after the other, until you develop a three-dimensional X-ray of how the fish is made inside by seeing how it ripples and how it sounds when it falls on the counter. And then [he] takes these knives that he always sharpens, and then starts cutting these fish so that he avoids the bone structure that would be in the way, and makes the thinner slices as fast as possible with the least effort possible. He developed this into an art form and is very proud every night. When he goes home, he knows that he has filleted better than anybody else could do in the world.”

A flow state can be entered performing any activity. However, it helps to do something. In other words, the most common example of an activity that is not conducive to flow state is watching TV. Although even for that, MC suggests that perhaps 7%-8% of the time one could access flow watching TV—if totally engrossed. One of my friends is particularly into screenwriting, and his delighted tracking of the story structure, elements and beats very likely elevates watching TV and movies to a flow-type of experience for him.

Still, for those of you who like a model, there is one to consider:

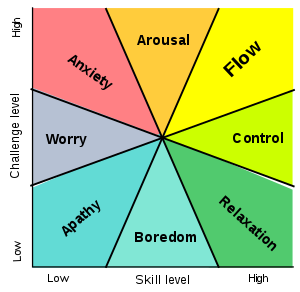

MC and colleagues published this model in 1987. Each of the 8 channels depicted represent the experience of different combinations of perceived challenge and perceived skill at a task. The most important takeaway is that flow is more likely to occur when the activity at hand is higher than average in perceived challenge, and the individual in question has above-average skills in relation to the task at hand. For MC, Arousal is a good place to be—as the learning process is likely to increase skill and lead to flow. Additionally, Control is a good place to be, as one can progressively increase the challenge to enter flow. Other commentators have noted that a clear set of goals and progress, immediate feedback, and confidence in one’s skill set are helpful.

Personally, I’ve found that I’m more likely to enter a flow state when engaged in activities that combine a physical component with a mental challenge. Note that the balance of the two is not particularly important—dancing after learning some challenging choreography can get me there, and writing about something I’m particularly passionate about can too. In the former situation, memory, dance steps/turns, and self-consciousness sort of slip away, and I can feel myself simply feeling, moving, and enjoying the moment. While writing in a flow state, ideas, concepts, illustrations, and phrases simply line up and burst from my head through my hands and onto the page—and I look at the clock, hours have disappeared, and whatever I was writing has flourished (at least in an initial draft form). I should point out that perceived skill and challenge level are important—I’m by no means an expert dancer—but flow is totally possible.

To increase happiness and heighten chances of success, it’s worth taking stock of our lives, and looking for opportunities on a regular basis to embrace and encourage a flow state. This could be in our workplaces (most likely to occur where goals are clear, feedback is immediate, and a balance between opportunity and capacity exists)[3], or in our leisure activities. If you’re having trouble, think of the last activity you got absorbed in. It could be painting, drawing, playing music, playing chess—whatever it is, do more of it. Schedule it if you have to. It may just be the key to happiness.

[1] For criticism, see Schneider, K. (2011). "Toward a Humanistic Positive Psychology". Existential Analysis: Journal of the Society for Existential Analysis. 22 (1): 32–38.

[2] Artistic and scientific creativity: Perry, (1999); Sawyer, (1992). Teaching: Csíkszentmihályi, Mihály (1996), Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, New York: Harper Perennial, ISBN 0-06-092820-4. Learning: Csíkszentmihályi et al., 1993. Sports: Jackson, Thomas, Marsh, & Smethurst, (2002); Stein, Kimiecik, Daniels, & Jackson, (1995).

[3] Csíkszentmihályi, Mihály (2003), Good Business: Leadership, Flow, and the Making of Meaning, New York: Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-200409-X.